By Laura Millar, MPH, M.A., MCHES

This article was written for Dr. Adam Graves’s class at San Francisco State University’s Program in Visual Impairments, in preparation for a panel discussion on how to incorporate sexual health education, bodily autonomy, and consent into the Expanded Core Curriculum.

Introduction: The Conversation We’re Not Having

When I was first diagnosed with Retinitis Pigmentosa and told that I was blind, I remember quietly wondering: Will anyone want to date me now? Will I still have a family? Is that future even possible anymore?

At the time, I didn’t have the language to name these feelings, but what I was experiencing was internalized ableism: the belief that disability makes you less worthy of love, intimacy, or pleasure. And I now know I wasn’t alone. Over the years, I’ve heard similar questions from students, parents, and peers who never had the opportunity to learn that their bodies are theirs, their desires are valid, and their voices matter.

Some of us had supportive, inclusive sexual health education, but too many others had only silence or shame. Society still struggles to talk openly about blindness and sexuality on their own, let alone together.

As you prepare to enter the field as teachers and educators of the blind and orientation & mobility specialists, you have an extraordinary opportunity and responsibility to change this narrative. This article isn’t about adding another curriculum to your already full plate. It’s about recognizing that you’re already teaching the foundational skills that support sexual health, autonomy, and healthy relationships every time you work with students on the Expanded Core Curriculum.

You don’t have to be a sex education expert to start these conversations. You just have to be willing to stay open and curious enough to have them. Because here’s the truth: whether or not we talk about sexuality, our students are already getting messages about their bodies, their desirability, and their autonomy. And those messages are shaped by childism and ableism.

This article will show you how sexual health education naturally integrates into the ECC work you’re learning to do, provide you with language and examples you can use immediately, and most importantly, give you permission to embrace this essential aspect of your future students’ lives.

Understanding Childism and Ableism and Their Impact on Sexual Health

Before we dive into practical applications, let’s establish a shared understanding of the systemic barriers we’re working against.

Ableism

Ableism is the systemic belief (often unspoken) that disabled people are less capable, less valuable, or less worthy than nondisabled people. It shows up in the lessons we skip, the assumptions we carry, and the silences we maintain. It’s the reason students learn to name the parts of a flower but not the parts of their own bodies. It’s why blind students are left out of conversations about attraction, gender, pleasure, or identity.

When students start believing those messages about themselves, that’s internalized ableism. It’s the quiet voice that says, “No one will want me,” or “I shouldn’t ask for what I want,” or “My body isn’t normal.”

Childism

Equally important, and often unexamined, is childism. One definition stated in the zine “NO! Against Adult Supremacy, Vol 1” states:

“Every hierarchy, every abuse, every act of domination that seeks to justify or excuse itself appeals through analogy to the rule of adults over children. We are all indoctrinated from birth in ways of ‘because I said so.’ The flags of supposed experience, benevolence, and familial obligation are the first of many paraded through our lives to celebrate the suppression of our agency, the dismissal of our desires, the reduction of our personhood. Our whole world is caught in a cycle of abuse, largely unexamined and unnamed. And at its root lies our dehumanization of children.”

Childism is the systematic devaluing and dismissal of children’s personhood, autonomy, and experiences simply because they are young. In the context of sexual health education, childism shows up when we:

● Refuse to answer students’ questions about their bodies because they’re “too young”

● Withhold anatomically correct language because we think children can’t handle it

● Dismiss students’ feelings, attractions, or identities as “just a phase”

● Make decisions about students’ bodies without their input or consent

● Assume students don’t need or deserve information about pleasure, boundaries, or autonomy

When childism and ableism intersect, blind children and youth face compounded marginalization. They’re told they’re too young to understand and too disabled to participate. Their questions are dismissed. Their autonomy is diminished. Their sexuality is either ignored entirely or treated as inappropriate, dangerous, or non-existent.

How These Show Up in Your Future Practice

In your future practice, you’ll encounter both ableism and childism in many forms:

● Parents who say, “My child doesn’t need to know about that”

● Colleagues who skip over sexual health topics in hygiene lessons

● Curricula that assume all students can see anatomical diagrams

● Healthcare providers who don’t make their materials accessible

● Students who’ve internalized the message that their bodies are shameful or that they’re not “relationship material”

● Adults who talk over students, make decisions for them, or dismiss their questions as inappropriate

Here’s what’s powerful about your role: None of us built these systems, but each of us can help dismantle them. As future educators of the blind, you’re positioned to interrupt these patterns early and consistently. You can model that blind students deserve complete information, that their bodies and desires are valid, that their voices and choices matter, and that autonomy begins with knowledge and respect.

A New Framework: Sexual Health is Already in the ECC

Sexual health isn’t just about reproduction or preventing risk. In its most comprehensive form, sexual health encompasses:

● Communication and self-advocacy

● Decision-making and consent

● Relationships and emotional intimacy

● Identity exploration (gender, orientation, attraction)

● Pleasure and bodily autonomy

● Safety and boundary-setting

● Health promotion and self-care

Look at that list again. These are the exact skills embedded throughout the Expanded Core Curriculum. You’re already teaching students to communicate their needs, make decisions about their bodies, navigate social interactions, advocate for themselves, and develop independence in daily living.

This isn’t about adding more to your plate. It’s about giving you permission and language to name what you’re already doing.

The PLISSIT Model: A Framework for Your Practice

To support you in this work, I want to share a model originally developed for psychosocial sexual counseling that has since been adapted to sexual health education. I’m now passing it on to you as parents, teachers, and educators of the blind, because this is useful information for everybody to have, especially people in positions of power working with children.

The PLISSIT model provides a framework for understanding the different levels of support you can offer students around sexual health:

P – Permission Giving

This is about creating a safe, shame-free environment where students know it’s okay to be curious, ask questions, and explore their bodies and identities. Permission giving happens when you use anatomical language casually, when you normalize bodily experiences, and when you affirm that students’ feelings and questions are valid.

Examples:

● Using words like “vulva” and “penis” matter-of-factly during hygiene lessons

● Saying “It’s normal to be curious about your body”

● Responding to questions without shock or discomfort

LI – Limited Information

This involves providing brief, accurate, factual information that directly addresses a student’s question or concern. You’re not giving a comprehensive sex education course in one conversation. You’re offering the specific information needed in that moment.

Examples:

● “Erections can happen randomly, especially during puberty. It doesn’t mean anything is wrong.”

● “Masturbation is when someone touches their own genitals because it feels good. It’s normal and private.”

● “People who menstruate usually start between ages 9 and 16.”

SS – Specific Suggestions

This level involves offering concrete strategies, skills, or solutions to help students navigate situations or challenges. You’re providing actionable guidance tailored to their specific circumstances.

Examples:

● Teaching how to track a menstrual cycle with accessible apps

● Practicing how to ask for accessible health information from a doctor

● Role-playing how to respond when someone violates a boundary

● Demonstrating how to open a condom package

IT – Intensive Therapy

This level involves ongoing therapeutic support for complex issues, trauma, or mental health concerns. This is beyond the scope of educators, but it’s crucial to know when a student needs this level of support and how to connect them with appropriate professionals.

When to consider referral:

● Student has experienced sexual trauma or abuse

● Student shows signs of significant distress around sexuality or body image

● Student has questions about sexual dysfunction or persistent pain

● Student needs support for gender dysphoria or identity-related mental health concerns

All four levels are valid and valuable depending on the situation. You don’t need to progress through them in order. Sometimes a student just needs permission. Sometimes they need specific suggestions immediately. Your role is to assess what level of support is most appropriate in each moment and recognize when to connect students with additional resources.

The following sections demonstrate how these levels of support naturally integrate into your ECC work. You’ll see PLISSIT in action throughout, sometimes explicitly noted and sometimes woven naturally into the examples. Pay attention to how permission giving, limited information, specific suggestions, and knowing when to refer can all happen within the contexts you’re already teaching.

Anatomy and Body Awareness

Why This Matters for Your Students

Students need clear, affirming language to describe their bodies, all parts of their bodies. That includes naming genitals like vulva, penis, and anus with the same comfort and ease we use for head, shoulders, knees, and toes. This is how we teach students that their bodies are whole, worthy of care, and not subjects to be avoided or considered taboo.

Anatomy education isn’t confined to biology class. It shows up in lessons on hygiene, in learning how to ask for help, in developing an understanding of sensation and consent, and in building body literacy. If a student doesn’t know the names of their body parts, how can they set boundaries, explore pleasure safely, or communicate with healthcare providers?

A Story from the Field

Early in my work as a sexual health professional in the blind community, I participated in a design sprint at General Assembly in San Francisco (circa 2016-2017). I was part of a panel discussing gaps in sexual health education, specifically the lack of accessibility and inclusion for blind and disabled individuals.

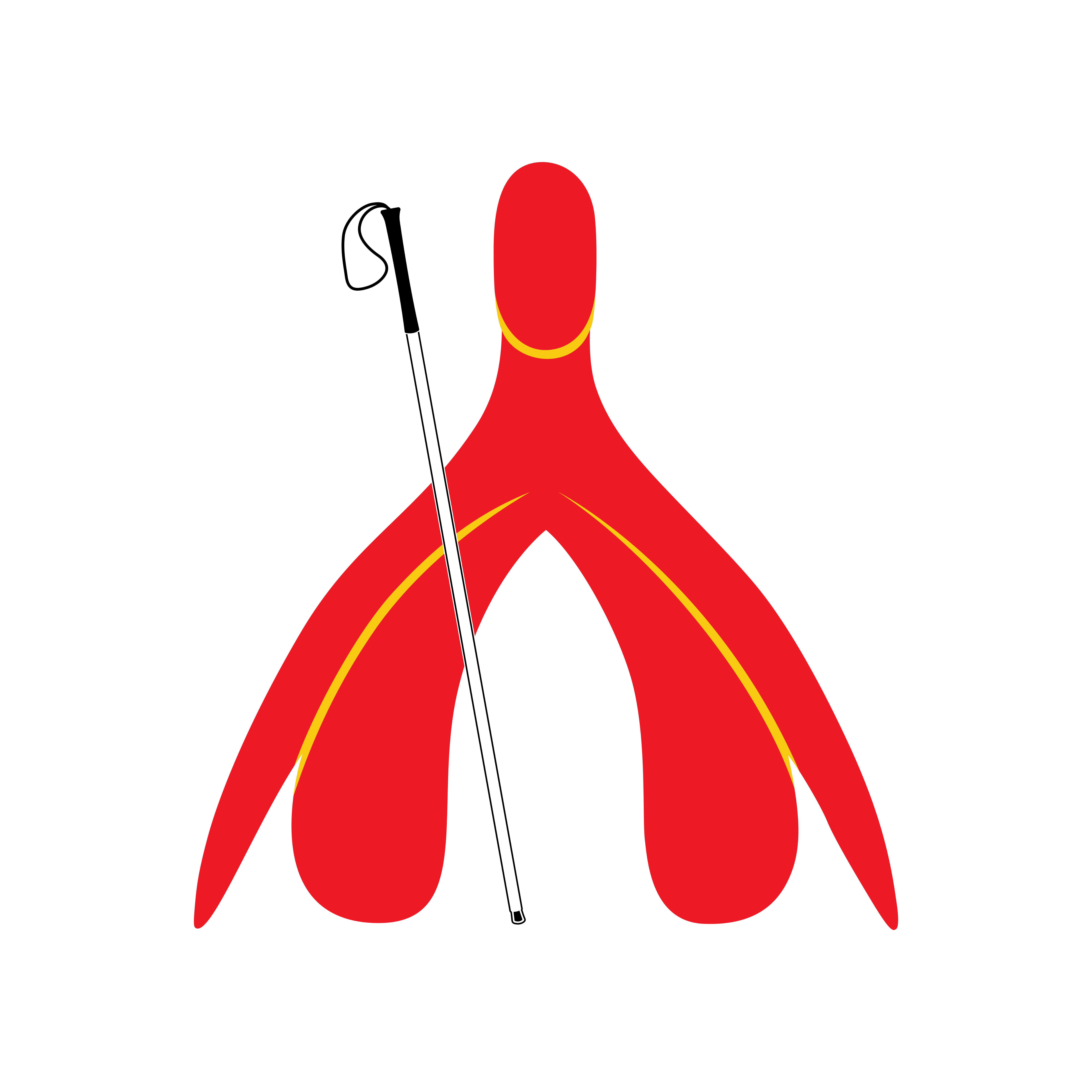

I held up a 3D anatomically correct model of the clitoris. For those who haven’t seen or felt one: the clitoris has an inverted Y or wishbone shape. The external part (the glans) is small and rounded, forming the top of the Y. But most of the clitoris is internal. Two elongated structures called the crura extend downward like the branches of a wishbone, and the vestibular bulbs form the base on either side of the vaginal opening. The whole structure is roughly the size of your palm when you make a peace sign.

I asked this room full of sighted individuals if anyone knew what I was holding. Only a couple of people raised their hands. As I passed it around, the response was overwhelmingly positive. A majority of the people in that room learned something about female anatomy that day. More importantly, they learned something about the needs of blind and disabled people when it comes to accessing information about sexual health.

Here’s the critical point: It wasn’t until 1998 that Australian urologist Helen O’Connell fully mapped the anatomical structure of the clitoris through cadaveric dissections and MRI scans. The first complete 3D sonography of the stimulated clitoris wasn’t published until 2008-2009. An organ that exists in roughly half the population was only fully understood by medical science at the turn of this century.

If sighted people with full access to visual diagrams don’t know this anatomy, how can we expect blind students to understand their bodies when we skip over these details or rely solely on visual materials?

That 3D clitoris model became one of my most valued teaching tools and eventually inspired my logo: a red anatomically correct clitoris holding a white cane, representing both blind positivity and sex positivity. I even imagined it as a character from Monsters Inc., complete with a cape and hood, using its super powerful sensing abilities to fight injustice. (Pixar, if you’re reading this, I have ideas.)

Where This Lives in the ECC

Compensatory Access:

Use tactile diagrams, 3D models, and audio descriptions that include all body parts, not just the ones considered “safe” or “appropriate.” Naming the clitoris is just as important as naming the wrist. Whether it’s a 3D-printed model, a tactile graphic, or a life-sized cardboard cutout, what matters is ensuring blind students have equal access to hands-on anatomy education.

These tools help students understand public versus private body parts without relying on visual diagrams. Important language note: Avoid phrases like “secret parts” because secrets imply shame. Instead, use words like private, personal, or shared with permission to promote agency and clarity.

Independent Living Skills (ILS):

Hygiene routines are natural opportunities to model comfort with anatomical language. If we hesitate to say “vulva,” students learn that shame is part of the lesson. If we say it casually while teaching bathing routines, they learn dignity.

Self-Determination:

When students are told that their whole body matters (not just the parts we’re comfortable discussing), they gain confidence to express discomfort, set boundaries, or explore safely on their own terms.

Assistive Technology:

Support students in using inclusive, accessible anatomy resources: screen reader-friendly websites, described models, and audio-based educational tools. AI, in particular, now offers a private and powerful way to learn about sex, pleasure, and boundaries. When I was young, I had to flip through medical journals in library stacks, hoping I was looking at the right diagrams. Today’s students with assistive technology skills can explore what many of us had to search for in silence, and that’s progress worth celebrating.

Modeling Permission and Language

This isn’t about memorizing scripts. It’s about modeling comfort and permission. This is Permission (P) in action. If you’ve ever sung “Head, shoulders, knees, and toes,” you already know how to list body parts. We’re just adding the parts that get left out:

“Head, shoulders, vulvas, penises, knees, and toes.”

When we model that it’s okay to say these words, we give students the power to say things like:

● “That’s my vulva. I don’t want it touched.”

● “I like my vulva!”

● “My penis feels tingly. Is that normal?”

● “My penis is private, for me only.”

● “My anus doesn’t feel good. What do I do?”

In hygiene lessons, you might say:

● “Let’s go over how to take care of your whole body when you shower or bathe. Wash behind your ears, under your arms, your vulva or penis, your anus, and your feet. Just like everything else, these parts need attention and care. If you have a vulva, you can gently wash the outside with warm water. No soap is needed on the inside because the vulva cleans itself.”

By teaching that talking about bodies is normal and healthy, we help students learn that every part of them deserves safety, care, and respect. Notice how this combines Permission (normalizing the language) with Limited Information (basic hygiene facts) without overwhelming the student.

Puberty and Body Changes

Why This Matters for Your Students

Puberty is a time of physical, emotional, and sensory change. Students might experience menstruation, erections, changes in skin, hair, voice, or even how they relate to touch or clothing. But this is not a “girls do this, boys do that” conversation. It’s a “bodies change in many ways” conversation.

Blind students deserve puberty education that reflects body diversity, doesn’t rely on visual cues, and doesn’t assume gender based on biology.

Where This Lives in the ECC

Independent Living Skills:

Teach how to manage new hygiene needs like period care, deodorant application, shaving, or changing underwear more frequently. This is where anatomy vocabulary becomes practical and essential.

Compensatory Access:

Many signs of puberty are visual (acne, breast growth, body hair patterns). Students benefit from descriptive information to understand these changes: “You might notice your chest feeling tender or fuller,” or “Most people’s skin produces more oil during puberty, which you might feel when washing your face or touching your forehead.”

Self-Awareness:

Help students notice and name how their body feels during changes, whether that’s physical arousal, increased body odor, emotional shifts, or new sensations. Encourage them to track patterns without judgment or shame.

Sensory Efficiency:

Support students in mapping body sensations like warmth, pressure, tingling, or tightness as non-visual indicators of puberty-related changes.

Modeling Permission and Language

Don’t wait for a student to bring it up. Model that puberty is an expected, welcome, and normal part of growing up. The following examples show how you can offer Limited Information that addresses common concerns without creating unnecessary anxiety:

Instead of: “All teenagers get moody going through puberty”

Try: “During puberty, your emotions might feel more intense or change more quickly. That could mean wanting more space sometimes, wanting more connection other times, or feeling things more deeply. All of that is normal.”

Instead of: “You’ll feel your body change”

Try: “You might notice new sensations: tingling, tenderness, or pressure in places like your chest, genitals, or belly. Those feelings are your body’s way of telling you it’s developing. You can always ask questions about what you’re experiencing.”

Instead of: “Girls get periods”

Try: “People who menstruate usually start sometime between ages 9 and 16. When that happens, we’ll figure out together what supplies work best for you, whether that’s pads, tampons, menstrual cups, or period underwear. We can create a supply kit so you’re prepared.”

Being clear and open about what bodies go through helps students understand their own needs and reduces fear or confusion about the changes they’re experiencing.

Consent and Boundaries

Why This Matters for Your Students

Consent is not just about saying no. It’s about being in charge of your body and your choices. It means knowing how to ask for something, how to pause, how to check in, and how to set or respect a boundary.

Students need to know that consent applies everywhere, not just in sexual contexts, but in shared spaces, friendships, conversations, and physical guidance during O&M instruction.

When students have the language of consent, understand it, and have opportunities to practice giving consent, setting boundaries, saying yes, and saying no, they are able to have more agency over their lives. When we model consent in action in real time, we give them skills and tools to navigate a lifetime of interactions.

The FRIES Model of Consent

To help students understand what healthy consent looks like, we can use the FRIES model. While this framework is often taught in sexual health contexts, it applies to ALL consent situations: from accepting help crossing a street to deciding whether to hug a relative to choosing whether to engage in sexual activity.

Consent should be:

F – Freely Given

Real consent happens without pressure, manipulation, or coercion. Students should never feel forced or guilted into saying yes. This applies to accepting physical guidance, participating in activities, or any other interaction.

R – Reversible

Anyone can change their mind at any time, even if they initially said yes. Students need to know they can withdraw consent whenever they feel uncomfortable, and that their “I changed my mind” is valid and must be respected.

I – Informed

Students need to understand what they’re agreeing to. This means having complete, accurate information before making a decision. Whether it’s understanding what will happen during an O&M lesson or what a social interaction involves, informed consent requires clarity.

E – Enthusiastic

Consent isn’t just the absence of a “no.” It’s an active, willing “yes.” Students should feel comfortable expressing genuine interest or agreement, not just going along to avoid conflict.

S – Specific

Saying yes to one thing doesn’t mean saying yes to everything. Consent for a high five doesn’t mean consent for a hug. Consent to try one intersection independently doesn’t mean consent to all intersections. Each situation requires its own consent.

Remember: FRIES isn’t just about sexual health. It’s about bodily autonomy, respect, and power in all interactions. When we give students the language and the name for what healthy consent looks like, when we identify what’s happening in real time, and when we work on solutions together, we end up with more empowered students.

Where This Lives in the ECC

Orientation & Mobility:

Model asking before offering touch, and invite students to choose how they want support:

● “Would you like to take my arm, or would you prefer I describe the environment while you navigate independently?”

● “I’m going to touch your shoulder to show you where the door handle is. Is that okay with you?”

● “Would you like to try this intersection on your own, or would you like me to walk alongside you this time?”

Social Interaction Skills:

Practice scripts for offering, declining, and adjusting contact or conversation:

● “I’m not comfortable with hugs, but I’d love a high five.”

● “Can we talk about something else? This topic is hard for me right now.”

● “I need you to stop touching my hair.”

Self-Determination:

Encourage students to make decisions about their comfort and trust themselves to stick to those decisions even when others are disappointed.

Career Education:

Teach how to set professional boundaries, respond to inappropriate questions, or handle discomfort with coworkers or supervisors.

Modeling Permission and Language

Consent education starts with adults asking students what they want. These examples demonstrate how Permission and Limited Information can be woven into everyday interactions:

● “Would you like help, or do you want to do it on your own?”

● “Do you want a high five, or would you prefer I just say congratulations?”

● “Do you want to keep talking about this, or take a break?”

● “Before we cross this street, how would you like to approach it? Would you like time to analyze the intersection together, or would you prefer to lead and I’ll follow your pace? You get to decide what feels right today.”

● “If someone ever touches you in a way that doesn’t feel good (even if you thought it would be okay when it started), you can always say, ‘I changed my mind,’ or ‘Please stop.’ Your feelings can change, and that’s completely okay.”

These phrases build a foundation. Students learn:

● They can choose how to approach tasks and interactions

● Their “no” is enough and deserves respect

● Their “yes” should be honest, freely offered, and can be revoked at any time

● Their “maybe” deserves time for reflection

A Story About the Power of “No”

I was working with a transitional age student on understanding consent and boundaries. We were discussing how consent works in various contexts, and I explained that anyone can say no at any time, even if they initiated the interaction.

They were shocked. They told me they thought that if they had started something (whether that was a conversation, a hug, or anything else), they had to follow through with it. The idea that their “no” was valid even after saying “yes” initially was completely new to them.

We had a deeper conversation about consent and boundaries and the power of their no. It was clear from this conversation that this information was coming a little too late, and at the same time, it was clear that it would likely change their life.

This wasn’t just about sexual situations. This was about them learning that they had agency over their life, their body, and their choices in every interaction. When we model consent in action in real time like this, we give students skills and tools to navigate a lifetime of interactions with confidence and self-respect.

When students struggle with boundary violations or show signs of trauma around touch, this may require Intensive Therapy level support. Know how to connect them with trauma-informed counselors who understand disability.

Masturbation and Privacy

Why This Matters for Your Students

Masturbation is a safe, common, and healthy form of self-exploration. But too often, blind students don’t receive direct information about it. Or worse, they’re punished for behavior that no one ever taught them was private.

Teaching about masturbation isn’t about encouraging it. It’s about removing shame and giving students tools to understand privacy, hygiene, and pleasure.

A Story from Practice

A family member and I were watching the TV show Speechless when a scene came on where a young character in high school was giving a speech in front of the entire school and experienced a spontaneous erection, which led to mortification and embarrassment. This young family member was trying to understand the context and what was happening.

This is a perfect example of where a parent or educator could gloss over the situation or use it as a teaching opportunity. We talked about erections, spontaneous erections, and even discussed some life advice on how to deal with shame or embarrassment when bodies do what bodies are gonna do. Because bodies are gonna do what bodies are gonna do.

These everyday moments are golden opportunities to normalize bodily experiences without making them a big, awkward “talk.”

Another Story: The Pancake Conversation

When I was a child, a family member was making pancakes one morning. I asked why we had to wash our hands before breakfast when we’d already taken a bath the night before. The response was simple: “Sometimes we touch ourselves at night.”

It wasn’t until years later that I realized this was about masturbation. But what I learned in that moment (without shame or discomfort) was that touching our bodies is normal, and washing our hands is just part of taking care of ourselves.

That brief, matter-of-fact exchange taught me more about healthy attitudes toward my body than many formal lessons could have.

Where This Lives in the ECC

Independent Living Skills:

Model handwashing, laundry routines, and cleaning up after personal care (including masturbation) without shame or awkwardness. Normalize that this is just another aspect of hygiene and self-care.

Self-Determination:

Give students permission to explore what feels good and decide what’s right for them. Bodily autonomy includes the right to pleasure.

Social Interaction Skills:

Help students understand privacy expectations in dorms, group settings, and shared spaces. What’s private at home might need different boundaries in other environments.

Recreation and Leisure:

Recognize that solo sensory pleasure (sexual or not) is part of how people unwind and connect with themselves.

Modeling Permission and Language

Many students aren’t given language for self-pleasure because we treat children, especially disabled children, as if they’re asexual or incapable of experiencing pleasure. Masturbation is rarely acknowledged in a developmentally appropriate way, and when it is, it’s often framed through silence or shame.

When a student touches themselves in a public setting, it’s not misbehavior. It’s a teaching moment. They may not yet understand what masturbation is or how to navigate private versus public behavior. This is an opportunity to offer Permission and Limited Information while providing Specific Suggestions for appropriate contexts:

● “That’s called masturbation, when someone touches their genitals because it feels good. It’s a normal and healthy thing many people do. It’s something private though, which means it should only happen in spaces where you’re alone with the door closed and no one can see in. If you have questions about it, I’m here to talk.”

● “If you’re alone in your room and you feel like touching your body to explore what feels good, that’s your private space. Just like when we brush our teeth or take a shower, we wash our hands before and after because it’s part of caring for ourselves.”

● “Sometimes our bodies become aroused. Your penis might get hard or your vulva might feel tingly or warm. This can happen when you’re relaxed, when you’re thinking about something pleasant, or even randomly for no clear reason. It doesn’t mean anything is wrong. It’s just your body working the way bodies work.”

For educators who don’t feel comfortable going into detail, that’s okay. You can still affirm the student and gently set boundaries without reinforcing shame:

● “That’s something that’s okay to do in private. If you ever want to learn more or have questions, I can help you find someone to talk to or share resources.”

You don’t have to say everything. But what you do say should affirm the student’s right to explore, experience, and learn about their own body in ways that are safe, private, and shame-free.

Relationships and Emotional Intimacy

Why This Matters for Your Students

Students deserve to understand how relationships form: how to express affection, build trust, and feel seen. Whether it’s friendship, romance, chosen family, or something else entirely, blind students deserve language and skills for intimacy in all its forms.

Where This Lives in the ECC

Social Interaction Skills:

Teach how to express interest, affirm boundaries, and build connection:

● How to ask someone to hang out

● How to tell if someone wants to continue a conversation

● How to end an interaction gracefully

● How to navigate rejection with dignity

Self-Determination:

Help students define what they want and desire in relationships, not what they think they should want.

Orientation & Mobility:

Navigate social spaces with intention: restaurants, coffee shops, group events. Practice how to meet people in various environments.

Recreation and Leisure:

Support access to blind-positive, queer-friendly, and accessible social spaces where students can meet others and build community.

Modeling Permission and Language

It’s important that students feel valued and supported as they explore relationships in various parts of their lives:

● “You are lovable. You are a desirable friend and companion. You are allowed to have feelings and act on them.”

● “If you like someone, you could say something like, ‘I really enjoy spending time with you. Would you want to hang out again sometime?’ You get to express what you’re feeling, and they get to respond honestly. Whatever their answer is, you were brave for asking.”

● “You might not get the exact kind of connection or intimacy you’re hoping for with someone. That’s okay. There may be other ways to stay connected and maintain a relationship with them if you both want that.”

● “It’s okay to feel disappointed when someone doesn’t feel the same way you do. But that doesn’t mean you were wrong to express your feelings or wrong to hope. You should feel proud of yourself for being brave enough to be honest about what you wanted.”

This approach helps students understand what they want and name it, not just to themselves but to others, without assuming what relationships “should” look like.

Gender Identity and Sexual Orientation

Why This Matters for Your Students

Students need to know that identity (including gender, orientation, and attraction) is personal, fluid, and valid. Blind students often don’t see themselves reflected in LGBTQ+ narratives or media. They deserve support to name who they are and what feels right to them without pressure to explain or conform.

Where This Lives in the ECC

Self-Determination:

Encourage students to define who they are without pressure to explain or conform to others’ expectations.

Recreation and Leisure:

Provide access to queer-blind-friendly media, spaces, and resources. Help students find community with others who share their identities.

Social Interaction Skills:

Practice inclusive language, asking and affirming pronouns, and navigating identity-based conversations with confidence.

Career Education:

Prepare students for navigating identity in the workplace: how to set boundaries, whether and how to disclose aspects of their identity, and how to respond to inappropriate questions.

Modeling Permission and Language

Students need compassion, kindness, and support as they explore various aspects of their identities. Remember, all levels of PLISSIT apply here. Sometimes students just need permission to explore. Other times they need specific resources or referrals.

Instead of: “Are you sure?” or “You’re too young to know”

Try:

● “You get to use the name and pronouns that feel most right to you, even if they change later.” (Permission)

● “Some people are only into one gender. Some are into many. Some people don’t feel romantic attraction at all. There’s no rule about how you have to feel.” (Limited Information)

● “When someone introduces themselves with they/them pronouns, use those pronouns naturally in conversation. For example: ‘Jordan said they’ll join us after lunch,’ or ‘I really appreciated their input on the project.’ It’s that simple. Just use the pronouns someone has shared with you.” (Specific Suggestions)

● “If you’re still figuring out what kinds of people you’re attracted to (or if you’re realizing you’re not attracted to anyone in particular), that’s completely okay. There’s no deadline for understanding yourself.” (Permission)

If a student is experiencing significant distress around their gender identity or sexual orientation, including depression, anxiety, or family conflict, they may benefit from Intensive Therapy with a counselor who specializes in LGBTQ+ affirming care and disability. Know how to connect them with these resources.

A Story About Knowing When to Refer

A young person came out to their family as transgender the week before our summer camp. Like all the other blind students at camp, they had needs around independence, orientation and mobility, and social connection. But they also had specific needs to understand their legal rights when it came to housing, employment, education, and healthcare as a transgender person.

I simply did not have enough knowledge to answer all of their questions. And that was okay.

That’s when you refer out and find resources. We were able to connect with the Transgender Law Center in Oakland, where I was able to not only help this young person get all the information they needed, but I also got an education myself. I learned about legal protections, name change processes, healthcare access, and resources I could share with future students.

It is definitely okay not to know everything. In fact, it’s probably best for everyone if you refer out when you’re uncomfortable or don’t know the answer. Recognizing the limits of your knowledge and connecting students with specialized support is not a failure. It’s good practice. It’s ethical. And it models for students that asking for help and seeking expertise is a strength, not a weakness.

Creating a safe environment for students to explore their identity helps them understand themselves and others, and lets them know they are valid and cared for whatever their realizations may be.

Reproduction and Contraception

Why This Matters for Your Students

Blind students need the same access as sighted students to learn how pregnancy happens, how to prevent it, and what options exist if it occurs. Teaching reproduction means making it real, tactile, and inclusive, not shaming, assuming, or skipping critical information.

This includes naming the options (like condoms, birth control pills, IUDs, and emergency contraception) and giving blind students hands-on experience learning how to access and use them.

A Critical Story About Access

A blind woman once shared with me the importance of understanding every aspect of your medication before leaving the pharmacy. She explained that she knew her birth control had a placebo week, but she didn’t understand the layout of the pill pack. Instead of taking the pills week by week (day 1 of week 1, day 2 of week 1, etc.), she took them by going across the top of the pack: week 1 day 1, week 2 day 1, week 3 day 1, week 4 day 1. Since week 4 day 1 was a placebo pill, she was essentially taking three active pills and one placebo every four days.

This is not how the instructions work. And this isn’t just about birth control. It’s about the critical importance of accessible medication information, proper labeling, and never assuming a student understands something just because they nodded or didn’t ask questions.

Where This Lives in the ECC

Independent Living Skills:

Teach students how to store, label, and access contraception with privacy and independence. Practice reading medication labels, setting reminders, and organizing supplies.

Compensatory Access:

Ensure tactile access to contraceptive options and full descriptions of how they work. This includes hands-on practice with condoms, feeling different types of birth control packaging, and understanding how to identify medications independently.

Self-Advocacy:

Help students learn to ask for information clearly and request alternative formats from healthcare providers:

● “Can you read that label out loud for me?”

● “Can I get the instructions in an accessible format?”

● “I need large print or braille labels for my medication.”

Assistive Technology:

Introduce accessible period or fertility tracking apps, birth control reminder apps, and other tools that support reproductive health management.

Modeling Permission and Language

Approach conversations about reproduction with a supportive and interested attitude. Here you’ll see how Specific Suggestions (hands-on practice) can be just as important as Limited Information:

● “Lots of people choose to have sex. Some want to get pregnant, and some don’t. If you ever want to know how to protect yourself or someone else from pregnancy or STIs, you deserve accurate and complete information.”

● “Knowing how to use a condom or other kinds of birth control is about being prepared, not about whether you’re sexually active right now. It’s a skill, just like knowing how to cook or take medication safely.”

● “Let’s practice opening a condom without tearing it, and identifying which direction it unrolls. That way, if you ever want to use one, you won’t be figuring it out for the first time in the moment.” (Specific Suggestions in action)

● “This is an example of a birth control pill pack. Most people who use birth control pills take one every day at the same time. If you’re ever interested, we can talk about which methods might work best for your body and lifestyle.”

A clear understanding of reproduction and birth control helps students make informed and conscientious decisions about their bodies and their lives.

STIs and Testing

Why This Matters for Your Students

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a normal part of health education. What students need is not fear, but facts and access. They need to know how infections spread, how to get tested, and how to communicate with partners and healthcare providers.

Where This Lives in the ECC

Self-Advocacy:

Teach students how to advocate with healthcare providers, request accommodations at clinics or pharmacies, and ask for information in accessible formats.

Community Access:

Prepare students to navigate STI clinics or telehealth appointments confidently and independently. Practice calling to make appointments, finding clinic locations, and using public transportation to get there.

Independent Living Skills:

Teach how to schedule and attend appointments, track health records, and follow up on care. This includes understanding test results and knowing when to seek follow-up treatment.

Assistive Technology:

Use accessible websites, health portals, and directories to learn about STI prevention and testing options. Teach students how to research clinics that offer accessible services.

Modeling Permission and Language

Be direct, respectful, and clear when talking about STIs. Avoid euphemisms like “being clean”:

● “Getting tested doesn’t mean you did something wrong. It means you care about yourself and your partners. It’s part of how we stay healthy.”

● “STIs are common, and most are treatable. Getting an STI doesn’t say anything about your value as a person.”

● “Want to practice calling a clinic to ask what accessibility options they have for blind patients? That way, you’re ready if you need it.”

● “You can say, ‘Can you read those results out loud for me?’ or ‘Can I get that information in an accessible format?’ You have a right to understand your own healthcare.”

Helping students navigate potential health concerns around sex reduces societal shame and stigma and empowers them to take better care of themselves and make informed decisions.

Pleasure and Communication

Why This Matters for Your Students

Students have the right to explore what feels good, to express what they like, and to talk about it. That includes sexual touch, non-sexual touch, emotional connection, and sensory input.

But pleasure education in this context isn’t just about sexuality or intimacy. It’s about modeling how students deserve to be treated in all aspects of their lives. When we teach students that their preferences matter, that comfort is important, and that they have the right to say “this feels good” or “this doesn’t feel good,” we’re teaching them that their sensory experiences and bodily autonomy are valid.

This shows up in simple, everyday interactions:

● “Would you like a firm handshake or a gentler one?”

● “Some people find this texture uncomfortable. How does it feel to you?”

● “You can adjust the temperature, lighting, or seating until it feels right for you.”

● “It’s okay to say when something doesn’t feel good, even if other people like it.”

Pleasure education means asking: What do you enjoy? What makes you feel good? How do you want to be touched? How do you want to be seen? These questions apply to every aspect of life, not just intimate relationships.

Where This Lives in the ECC

Social Interaction Skills:

Teach students how to talk about preferences, offer feedback, and check in with others:

● “I really like when you hug me like this.”

● “That doesn’t feel good to me. Could we try something different?”

● “Can I hold your hand?”

Self-Determination:

Support students in making decisions about what feels good to them, not what they’re told they should want or enjoy.

Sensory Efficiency:

Invite students to track and understand their body’s response to different types of touch and sensory input. Help them develop language for what feels pleasant, uncomfortable, or neutral.

Recreation and Leisure:

Recognize that joy, comfort, and arousal are part of leisure too, not just function or care.

Modeling Permission and Language

It’s easy to focus on what isn’t supposed to happen, but that can lead to anxiety and shame about desire and pleasure. Instead, try:

● “You deserve to feel good. You’re allowed to explore what that means for you.”

● “Pleasure looks different for everyone. There’s no right way to feel desire or express it, as long as everything is done with consent.”

● “Some people like gentle touch. Some people like firm pressure. Some people like to be alone with a warm blanket. These are all forms of pleasure, and you get to figure out what yours looks like.”

● “You can say, ‘I like when you hold me here,’ or ‘That doesn’t feel good. Can we try something different?’ That kind of communication makes touch and physical intimacy better and more respectful.”

Giving students tools to talk about and explore pleasure empowers them to be curious and to discover how to find and foster it in themselves and with others.

Body Image and Self-Esteem

Why This Matters for Your Students

Body image is a core topic in comprehensive sexual health education, but too often, it’s reduced to conversations about weight, appearance, or puberty. For blind students, the stakes are different. We all grow up surrounded by messages about what bodies are “supposed” to look like, but blindness is almost never depicted in a positive light. It’s absent from health education materials, stigmatized in media, or presented as something to pity or overcome.

This lack of representation fuels ableism (the belief that non-disabled bodies are more valuable) and often leads to internalized ableism, where students begin to believe their own bodies are “less than” or undeserving of attention, care, pleasure, or confidence.

In sexual health education, body image must go deeper than appearance. We must talk about how blind students experience their bodies: through movement, sensation, emotional connection, interdependence, and pride.

We shift the focus from what bodies look like to what they do, how they feel, and how students can learn to trust and appreciate their bodies in a world that often excludes them.

Where This Lives in the ECC

Self-Awareness:

Support students in noticing how they feel in their bodies, not just how others might perceive them. Help them develop language to describe comfort, pride, dysphoria, sensory overwhelm, or embodiment.

Social Interaction Skills:

Teach students how to identify and interrupt body-shaming language, whether directed at themselves or others. Encourage them to affirm one another through inclusive, non-appearance-based compliments and care.

Recreation and Leisure:

Offer opportunities for creative expression and joyful movement that emphasize how a body feels, not how it looks. Dance, adaptive sports, yoga, and tactile arts can all support embodied self-esteem.

Career Education:

Prepare students to present themselves confidently in professional settings without feeling pressure to hide or downplay their blind or disabled identity. Discuss clothing choices, grooming, and communication in ways that affirm their body and identity.

Modeling Permission and Language

We model positive body image through what we say and what we do (and don’t do) with our bodies. These responses offer Permission and Limited Information while validating students’ experiences:

● “Your body is not the problem. The way people treat you might be uncomfortable, but your body is good.”

● “What’s something your body helped you do this week that made you feel proud?”

● “That’s a really common stereotype. But blind people have all kinds of bodies, just like everyone else. You deserve to feel good in yours.”

● “There’s no one right way to look or move or be. What matters most is that you get to decide how you feel in your own body. Your body is already enough.”

Building comfort in students helps them move with greater confidence through a world that too often is not accessible or accommodating, and allows them to advocate more easily for themselves and their needs.

If a student shows signs of disordered eating, extreme negative self-talk, self-harm, or severe body dysmorphia,these concerns require Intensive Therapy beyond what educators can provide. Connect them with mental health professionals who understand both disability and body image issues.

Closing: What We Teach When We Teach It All

When we talk about sex, pleasure, boundaries, and bodies, we’re not teaching something extra. We’re teaching self-worth. We’re teaching power. We’re teaching love.

The Expanded Core Curriculum has always been about autonomy, access, and independence. This is just the next step.

Coming Back to Where We Started

Remember at the beginning of this article when I shared my own question after being diagnosed: Will anyone want to date me now? Will I still have a family? That internalized ableism, that fear, that silence didn’t have to be my story. And it doesn’t have to be your students’ story either.

Maybe right now you’re thinking: “But this isn’t my field. I’m not a sex educator. What if I say the wrong thing? What if I don’t know the answer?”

That’s exactly why we gave you the PLISSIT model.

You don’t need to be an expert in sexuality to support your students in this area. The framework shows you exactly what’s within your scope:

● Permission is just creating a shame-free environment and using accurate language

● Limited Information is answering direct questions with brief, factual responses

● Specific Suggestions is teaching practical skills you’re already equipped to teach

● Intensive Therapy is knowing when to refer out, just like you would for any other specialized need

When that young person came to camp having just come out as transgender, I didn’t have all the answers about legal rights and healthcare access. But I knew how to connect them with the Transgender Law Center. That wasn’t a failure. That was good practice.

When I worked with the transitional age student who didn’t know they could say no after saying yes, I didn’t need a PhD in sexuality. I just needed to model consent, provide language, and have an honest conversation with them about the power of their no.

You already do this work. Every time you ask a student, “Would you like to take my arm, or would you prefer to navigate independently?” you’re teaching consent. Every time you teach hygiene and name all body parts without shame, you’re giving permission. Every time you help a student advocate for accessible materials, you’re building the exact skills they need to advocate for their sexual health.

Dismantling Childism and Ableism Together

When we give students the language for childism and ableism, when we identify what’s happening, when we work on solutions together, we end up with more empowered students. The same is true for consent, for pleasure, for identity, for all of it.

Both childism and ableism teach students that their voices don’t matter, that adults and professionals know better, that their bodies aren’t truly theirs. When we interrupt these patterns by respecting students’ autonomy, answering their questions honestly, and treating them as whole people deserving of complete information, we break the cycle.

Your students deserve to know:

● That their bodies are good

● That pleasure is not shameful

● That they can say yes, no, or maybe, and change their minds

● That they are worthy of love, connection, and respect

● That blind people have rich, fulfilling sexual and romantic lives

● That asking for what they want is a strength

● That their boundaries matter

● That their questions are valid, not inappropriate

● That they have the right to information about their own bodies and lives

As you prepare to enter the field, remember: you don’t need to be a sexuality expert to support your students in this area. You already have the PLISSIT framework to guide you. You just need to be willing to:

● Give Permission by using accurate language for all body parts without shame and normalizing conversations about bodies and pleasure

● Provide Limited Information that’s factual, brief, and directly responsive to students’ questions and developmental needs

● Offer Specific Suggestions through role-playing, hands-on practice, and concrete strategies students can use

● Know when to refer for Intensive Therapy when students need support beyond your scope

● Model consent in every interaction, from O&M lessons to classroom conversations

● Interrupt ableism and childism when you see them, in curricula, in colleague comments, in student self-talk

● Trust that your students are whole people who deserve complete information about their bodies, their rights, and their potential for connection, pleasure, and love

Don’t wait for a perfect script. Don’t wait for permission from a supervisor or a curriculum guide. Don’t wait until you feel like an expert.

Start with what you already know:

That your students are worthy of care.

That they have a right to their bodies, their boundaries, their pleasure, and their joy.

And that you’re already the kind of educator who is brave enough to teach it.

Let’s not wait. Let’s begin.

About the Author

Laura Millar, MPH, M.A., MCHES, is a co-founder of the Blind Sexuality Access Network (BSAN), a growing network of blind professionals and community members dedicated to expanding the conversation around sexuality in the blind community. As a blind queer mother navigating multiple disabilities and chronic illnesses, her personal experiences enrich and shape her professional expertise. She holds a Master of Public Health and a Master of Arts in Human Sexuality from San Francisco State University and is a Master Certified Health Education Specialist. Her work focuses on dismantling ableism in sexual health education for blind people of all ages through coaching, consultancy, research, and community organizing.

Her logo features a red anatomically correct clitoris holding a white cane, representing both blind positivity and sex positivity at the intersection of her work.

Connect and Get Involved:

Follow the Blind Sexuality Access Network in the new year to learn how to get plugged into the network and join the conversation. Visit www.lauramillar.com and www.blindsexualityaccessnetwork.org, or support this work through Laura’s Patreon.

Author’s Note

This post was written and compiled with the support of artificial intelligence. While AI assisted with organization, formatting, and editing, the heart of this piece comes from a much deeper collective source. These words are my own, but the wisdom within them is shared, drawn from generations of disabled advocates, organizers, and disability justice leaders whose work and lived experience have shaped the language of access, equity, and liberation. They have been an integral part of my personal and professional journey. I write from their shoulders, carrying forward what they have taught us: that access is love, and that justice begins with the courage to listen, learn, and act.